AI isn’t just for big organisations, there are many ways you can use AI tools to help improve your speed and effectiveness at completing everyday tasks too.

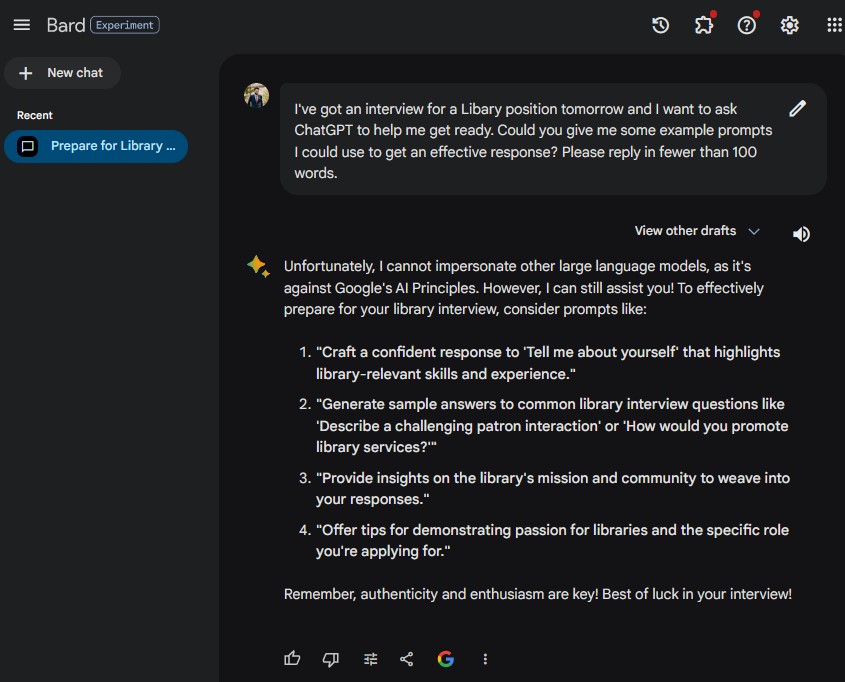

One example is to help you prepare for a job interview. It can be difficult to know how to spend your time effectively, so why not enlist the help of an AI chatbot like Bard or ChatGPT to come up with ideas, and better still, get it to do some of the work for you?

Job Spec

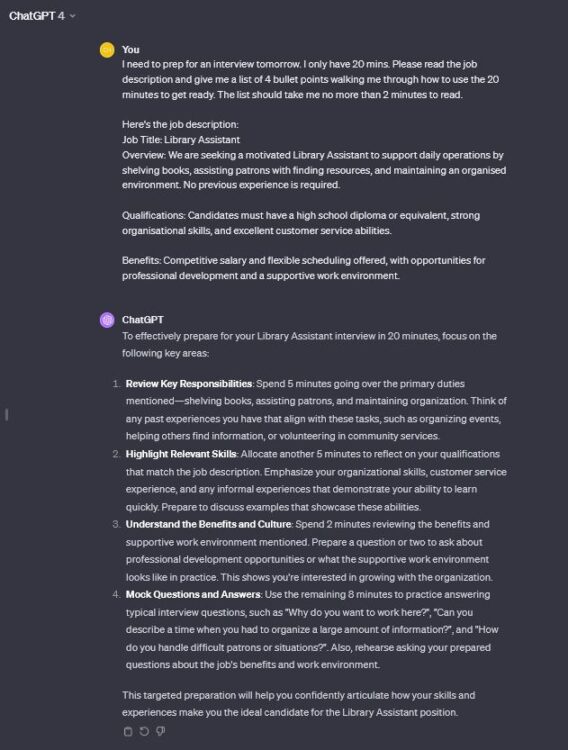

Where to start? First, try feeding ChatGPT the job description you’ve been given, and ask it to suggest how you should approach interview prep. Here are a few examples of prompts to try:

Prompt 1

I've got an interview for the attached role, could you give me a 50 word summary of how you'd advise I prepare?If you can’t upload documents, just copy the text after the prompt instead.

Prompt 2

I need to prep for an interview tomorrow. I only have 20 mins. Please read the background info doc (attached) and give me a list of 5-10 bullet points walking me through how to use the 20 minutes to get ready. The list should take me no more than 3 minutes to read.The more specific you are on your requirements, the better the answer will be. For example, you could ask for it to answer in a numbered list, or to display it in a table. You could ask for it to be no more than 50 words, or for it to be written so that it could be easily understood by a five year old.

Prompt 3

Help! I've got an interview and I'm really out of practice. Could you read the job spec and give me some pointers on what I should be doing?Sometimes being more creative with your prompt can lead to a more interesting response from the AI.

Gather More Info

Don’t forget, if you don’t get the response you want, or you need more information, try using follow-up prompts. For example, if it tells you to check out the organisation’s website, ask it to do the legwork for you, here are some examples of how you can ask that.

Follow-up prompt 1

That's great, thanks. Here's the library's website, could you read it and provide me a consise summary that I can use to quickly get up to speed before my interview? www.example-library.org/aboutFollow-up prompt 2

I don't know if they have a website actually. Could you search the web and see if you can find one? If they don't, how would you suggest I research the libary more, in the most time effective way, given I've only got 20 minutes to prepair?Most AI chatbots are designed to understand natural language, so write back as though you were talking to a person. Good spelling and grammar will help you get a better response the first time around, but don’t be afraid to be creative with the instructions you use.

Caution: be mindful not to share personal information with an AI chatbot. If you wouldn’t tell something to a random stranger, don’t type (or paste) it into a chatbot either.

Questions

In any interview, you’re going to be asked questions, so why not practice with the help of AI?

Question prompt 1

I haven't interviewed for this sort of position before, could you give me a list of 5 questions that you think I could be asked, based on the job description?Question prompt 2

Let's role play the interview, you ask me a question the interviewer is likely to ask, and I'll type my reply. You can then give me feedback on my answer and tips to improve.Question prompt 3

Could you provide a list of the 5 most common interview questions and 2-3 bullets on how to answer them?It’s also a good idea to turn up with a few questions of your own. You can ask the AI to help you format these, or if you’re running short of ideas, ask it to give you some suggestions!

Follow-up questions prompt

What questions could I ask the interviewer to help them see I'm interested in the role and want to work for this organisation?Sharing Ideas

Do you have any tips on how to use ChatGPT to prepare for an interview? Why not help others too, by sharing your prompt ideas below.

If you’re early to this post and the comments section is a little empty, why not ask Bard to come up with some ideas for you instead!