What is Ecosia?

Simply put, Ecosia is a search engine that plants trees with its profits.

💻📱 👉 💷💲 👉 🌱🌳

Which Search Engine Does Ecosia Use?

Ecosia is an organisation and search engine in its own right, but its results are powered by Microsoft Bing. Bing itself is carbon neutral and the whole of Microsoft are looking to go green by committing to be carbon negative by 2030.

How Green is Ecosia?

Ecosia recognise the impact the internet has on the environment of our planet. Ecosia runs on renewable energy, meaning your searches aren’t negatively impacting the planet.

“If the internet were a country it would rank #3 in the world in terms of electricity consumption” – Ecosia, 2018

In fact, searching with Ecosia is actually positively impacting the planet, with each search removing CO2 from the atmosphere. How? Because they plant trees with their profits.

As mentioned above, Bing (which powers Ecosia) is carbon neutral, so searching using Ecosia is a win-win from the perspective of your carbon footprint 👣

How Does Ecosia Make Money?

Like Google, Ecosia don’t make money from search results, they make their revenue from the ads that sit alongside the results.

Every time you click on an advert on Ecosia, you contribute to their revenue, which ultimately leads to trees being planted somewhere around the world

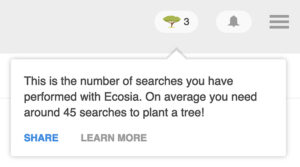

They have a helpful counter on their search results to show you how many trees you’ve personally contributed towards.

So far they have planted over 100 million trees worldwide, supporting projects in 15 countries.

Why am I Promoting Ecosia?

The reason I wrote this article is because I think Ecosia awesome. They’re an organisation trying really hard to do the right thing and they’re clearly having an impact.

Congrats Ecosia on your success and thank you for what you’re doing for the world 🙏🎉🎊

Ecosia.org 🌍 give it a go 😊