How many human brains would it take to store the Internet?

Last September I asked if the human brain were a hard drive how much data could it hold?

I concluded that approximately 300 exabytes (or 300 million terabytes) of data can be stored in the memory of the average person. Interesting stuff right?

I concluded that approximately 300 exabytes (or 300 million terabytes) of data can be stored in the memory of the average person. Interesting stuff right?

Now I know how much computer data the human brain can potentially hold, I want to know how many people’s brains would be needed to store the Internet.

To do this I need to know how big the Internet is. That can’t be too hard to find out, right?

It sounds like a simple question, but it’s almost like asking how big is the Universe!

Eric Schmidt

In 2005, Executive chairman of Google, Eric Schmidt, famously wrote regarding the size of the Internet:

“A study that was done last year indicated roughly five million terabytes. How much is indexable, searchable today? Current estimate: about 170 terabytes.”

So in 2004, the Internet was estimated to be 5 exobytes (or 5,120,000,000,000,000,000 bytes).

The Journal Science

In early 2011, the journal Science calculated that the amount of data in the world in 2007 was equivalent to around 300 exabytes. That’s a lot of data, and most would have been stored in such a way that it was accessible via the Internet – whether publicly accessible or not.

So in 2007, the average memory capacity of just one person, could have stored all the virtual data in the world. Technology has some catching up to do. Mother Nature is walking all over it!

The Impossible Question

In 2013, the size of the Internet is unknown. Without mass global collaboration, I don’t think we will ever know how big it is. The problem is defining what is the Internet and what isn’t. Is a businesses intranet which is accessible from external locations (so an extranet) part of the Internet? Arguably yes, it is.

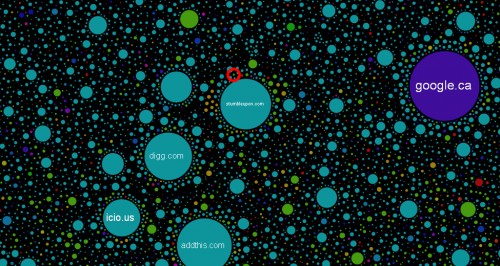

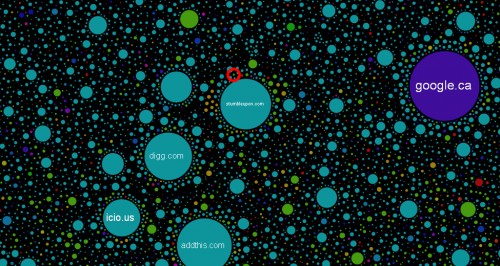

A map of the known and indexed Internet, developed by Ruslan Enikeev using Alexa rank

I could try and work out how many sites there are, and then times this by the average site size. However what’s the average size of a website? YouTube is petabytes in size, whilst my personal website is just kilobytes. How do you average that out?

See the red circle? That is pointing at Technology Bloggers! Yes we are on the Internet map.

The Internet is now too big to try and quantify, so I can’t determine it’s size. My best chance is a rough estimate.

How Big Is The Internet?

What is the size of the Internet in 2013? Or to put it another way, how many bytes is the Internet? Well, if in 2004 Google had indexed around 170 terabytes of an estimated 500 million terabyte net, then it had indexed around 0.00000034% of the web at that time.

On Google’s how search works feature, the company boasts how their index is well over 100,000,000 gigabytes. That’s 100,000 terabytes or 100 petabytes. Assuming that Google is getting slightly better at finding and indexing things, and therefore has now indexed around 0.000001% of the web (meaning it’s indexed three times more of the web as a percentage than it had in 2004) then 0.000001% of the web would be 100 petabytes.

100 petabytes times 1,000,000 is equal to 100 zettabytes, meaning 1% of the net is equal to around 100 zettabytes. Times 100 zettabytes by 100 and you get 10 yottabytes, which is (by my calculations) equivalent to the size of the web.

So the Internet is 10 yottabytes! Or 10,000,000,000,000 (ten thousand billion) terabytes.

How Many People Would It Take Memorise The Internet?

If the web is equivalent to 10 yottabytes (or 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 bytes) and the memory capacity of a person is 0.0003 yottabytes, (0.3 zettabytes) then currently, in 2013, it would take around 33,333 people to store the Internet – in their heads.

A Human Internet

The population of earth is currently 7.09 billion. So if there was a human Internet, whereby all people on earth were connected, how much data could we all hold?

The calculation: 0.0003 yottabytes x 7,090,000,000 = 2,127,000 yottabytes.

A yottabyte is currently the biggest officially recognised unit of data, however the next step (which isn’t currently recognised) is a brontobyte. So if mankind was to max-out its memory, we could store 2,127 brontobytes of data.

I estimated the Internet would take up a tiny 0.00047% of humanities memory capacity.

The conclusion of my post on how much data the human brain can hold was that we won’t ever be able to technically match the amazing feats that nature has achieved. Have I changed my mind? Not really, no.