On Sunday I will be lifting off into the wild blue yonder once more for a quick scoot across the Atlantic from Boston to Dublin and on to Milan. This is a rather regular occurrence nowadays. Flying is part of my life and for the kids, who have been on more aircraft than trains.

The environmental impact of all of this folly though is tied up in a rather controversial debate. On the one hand we have those who say that airline carbon and pollution emissions is minimal, others disagree. It seems that between 2 and 5% of possible global warming type emissions come from aviation. Not a lot we might think, when we bear in mind that 10% comes from car use, and about 17% from agricultural food production, but we all eat, we do not all fly.

This year the European Union was to start taxing airlines on their carbon emissions, in line with the way they tax other industry on theirs. This might seem fair to some, not to others, particularly large airlines and countries. Here in the USA a law was passed to state that US airlines could not participate in the scheme, and so could not pay the tax. China, India and others followed, and so the scheme has been postponed.

So back to my flight on Sunday. Between us, I and my family will produce about 12 metric tons of carbon dioxide in our time in the air. The average European produces about 10 a year, Americans more like 19 0r 20 and the average African about 0.3 tons per year.

Oh to put things in perspective the global average is 1.3 metric tons per year per person, and the 1.1 billion people who live on the continent of Africa produces about 7% of the emissions that the 0.6 billion population of North America produce.

So taken in terms of people and not percentages, flying is extremely polluting. But people are not going to stop flying. The aviation industry is ever expanding, even vegetables fly nowadays.

One way that aircraft engineers are trying to cut down on emissions is to design lighter and more fuel efficient engines. Weight is a big problem in flying, and it is our old friend 3D printing who might come to the rescue.

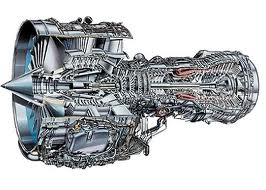

A company called CFM International, a joint venture between GE Aviation and the French company Snecma, has created the LEAP engine — an acronym for “leading edge aviation propulsion” that the company hopes reflects just how innovative the new aircraft component is. LEAP has many futuristic features, including a 3-D-printed nozzle, the part of the plane responsible for burning fuel.

3D printing allows engineers to produce objects in materials that either would be too expensive or impossible to make using conventional techniques, and they can use lightweight materials or ceramics as is the case with the new CFM engine to substitute heavy metal parts. Check out this article in CNN for details.

Over the last couple of weeks an aeroplane has made a trans America flight using solar power, and this is just part of its round the world trip. A whole new concept in low carbon emission flight, although currently a bit slow.

Another possibility is to use organic jet fuel. Although this may seem strange, as long ago as 2009 Air New Zealand conducted a test flight using an organic jet fuel mix that seemed to demonstrate a 60% cut in carbon emissions.

Here is a link to an article in the New York Times about aviation and carbon developments and some more data about carbon emissions in Africa if I have tickled your interest. And as always, I am all ears.